Fats Fernlund was born in July 1922 in the Cayuna Iron Range town of Crosby, MN. The second son of Swedish immigrants, he had curly blond hair and blue eyes.

No one knows how he earned the nickname Fats; odds are, it was because he was a big Swede. He probably didn’t mind that moniker since it kept his middle name, Sherwood, out of public view.

Like many other children in Crosby, Fats’ family was deeply connected to the mining industry. His father and uncles toiled in the underground mines, a fact that shaped his early life. He would see his father return home, six days a week, from his grueling twelve-hour shift, setting dynamite and exploding the rock face that contained the iron ore that helped build America. He’d lay down on the living room floor of their modest, company-built house, demanding the kids remain silent, hoping to make the headaches go away.

Fats knew the mining life wasn’t for him.

Before the end of the Great Depression, Ma and Pa Fernlund bought a farm and moved away from mining. They raised turkeys for a while until a blizzard killed the flock one winter. They had turkey for breakfast, lunch, and dinner until the Spring thaw. Fats always said that season was why he didn’t like turkey and wouldn’t eat it, even on Thanksgiving.

The move to the farm meant his high school career would be at Pequot Lakes High School. An outstanding football player, he was scouted by colleges. Insane governments in Germany and Japan put an end to his college dreams.

After a stint as a small-town Minnesota boy building warplanes in California, he tried to join the Army Air Corps. Big Swede that he was, the Army didn’t consider him appropriately sized for riding in an aircraft, but they found a use for him in the Philippines.

I first met Fats in 1954. He’s my dad.

My dad never really talked about his experiences in the Philippines. Like many veterans, he found it best to try and forget what he’d been through.

I learned to be highly cautious when waking him from a pre-supper nap. The first time I went into my parents’ bedroom and poked him to wake up, I found myself at the wrong end of his fist. He attributed that knee-jerk reaction to his time on troop ships and tropical barracks, when sleep was a precious commodity. Poke and run was my solution to staying healthy when Mom said, “Supper time, go wake Dad.”

When I was a wee lad, my dad’s brother, Kenny, lived with us for a time. Getting up early, I was allowed to join them at the kitchen table as they listened to WCCO radio and smoked cigarettes before going to work. They let me slurp down some Folgers. I still smoke and drink coffee, and I miss those two guys. My smartphone takes the place of ‘CCO.

I did a few stupid things growing up, as we all do, but I always felt Fats was proud of me. He was most proud of the grandkids the Bohunk and I gave him. Nothing delighted him more than taking each of them out for a one-on-one “businessman’s lunch” on their birthday. The kids loved it, too.

Fats had humble expectations his whole life. Family and friends were the most important things for him.

He taught me how to fish, play baseball, and drive, even though I was still a few years shy of 16.

For as long as I knew him, he never touched a gun. Maybe it was a result of his war experience. He never said. But he made sure I had the proper National Rifle Association training before I was allowed to get a rifle in my early teens.

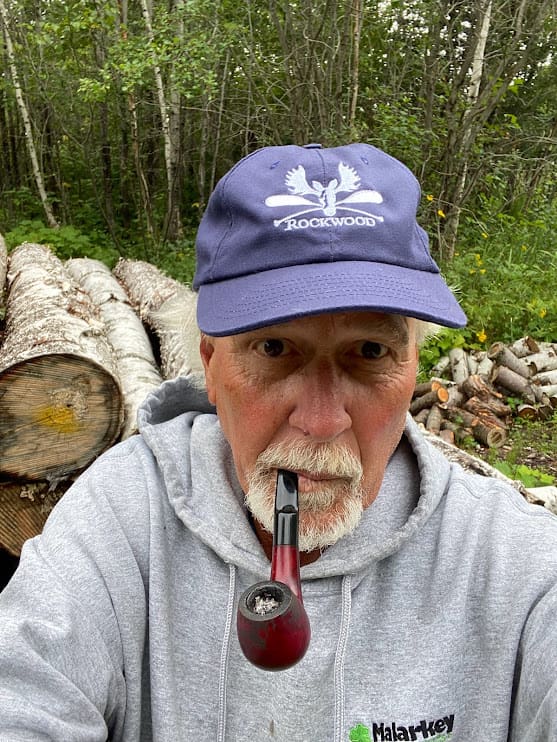

Fats died in 1995, just a few days before we moved to Grand Marais. I have his wedding picture on my nightstand, and I miss him every day.

To one and all, Happy Father’s Day this weekend.