According to a report aired last October on Minnesota Public Radio, the Reserve Mining Company of Silver Bay engaged in the practice of dumping waste rock and sediment from their ore operation directly into Lake Superior from 1955 to 1974. The practice persisted for 25 years, at a rate of 47 tons of waste material per minute, seven days a week. The sediment and sludge dumped from Reserve’s mining and processing operations turned the waters around Silver Bay to a muddy gray-green color and fouled Lake water 50 miles away in Duluth, causing concern among residents and city leaders alike when water analysis revealed that “asbestos like fiber” that “might cause cancer” was present in Duluth’s drinking water. As with the current divide in public opinion on the crisis of climate change, there were those in 1974 who were alarmed about what they saw happening to the beautiful, pristine waters of Lake Superior and those who thought the practice posed no real threat to the environment. The court case that ensued ignited one of the first battles of the Environmental Movement.

The trial began with government scientists arguing that Reserve’s sludge was spreading “a plume of pollution across the western end of Lake Superior,” and that “the asbestos-like particles in city water supplies could pose a significant health risk to residents.”

Reserve Mining’s experts disagreed, saying that “the fibers in the waste rock were not identical to asbestos,” and that “people were not being exposed to enough of the fibers to cause a health concern.” The trial lasted eight months and arguments from both sides were heated. The short version of this portion of the story is that presiding Judge, Miles Lord, found the legal team from Reserve to be less than transparent in their arguments. He finally asked Reserve Chairman C. William Verity to stop polluting the lake, the air and “poisoning the people downstream,” to which Verity responded, “We don’t have to, we won’t.”

Judge Lord ordered Reserve to immediately stop dumping its waste into Lake Superior. This was the first time that a Judge risked a major industrial plant shut down to protect the environment. Reserve Mining threatened to close its Silver Bay operation and put 3000 local residents out of work. The company also appealed the decision.

The Federal Court of Appeals reversed Judge Lord’s decision and allowed Reserve to continue to dump tailings into Lake Superior until another waste site was found. Minnesota state agencies (the Department of Natural Resources and the Pollution Control Agency) conducted a nine month contested case hearing and concluded that another tailings basin location would be a less risky alternative than the Mile Post 7 site, which is located 3 miles northwest and 600 feet above Silver Bay, Beaver Bay and Lake Superior.

Fast forward to 2020, when Northshore Mining, owned by Cleveland-Cliffs, announced plans to expand the Mile Post 7 facility which currently holds 40 years worth of tailings waste.

Concerns about safety, the long term operation of the facility and the possibility of human and environmental destruction in the event of a catastrophic failure have raised serious questions among both residents and environmental organizations.

It should be noted that the Mile Post 7 dam is a class 1 dam and it is no wonder that there is and should be public concern. According to the Minnesota Revisor’s office, a class 1 dam means that failure of the dam could “cause loss of life, serious hazard or damage to health, main highways, high-value industrial or commercial properties, major public utilities or serious direct or indirect, economic loss to the public.” In May of last year, Paula Maccabee, Advocacy Director and Council for WaterLegacy, a grassroots advocacy group based in Duluth, sent a communication to Bill Johnson, Mining Planning Director for the Minnesota DNR, requesting a new Environmental Impact Study (EIS) and outlining the findings of the EIS from 1976.

That original EIS recommended that a different site for the tailings dam be chosen because of the “potential for significant environmental effects of a dam breach at Mile Post 7.”

Those effects were described as follows. “A 1000 foot breach in the south dam at Mile Post 7 would produce a 28 foot high wall of water moving down the Beaver River valley at more than 20 miles an hour to Lake Superior. The EIS from 1976 also acknowledged that in the event of dam failure, “significant water resources would be destroyed, impaired and polluted” and that “the threat to Lake Superior would not end when operations cease but would persist indefinitely.”

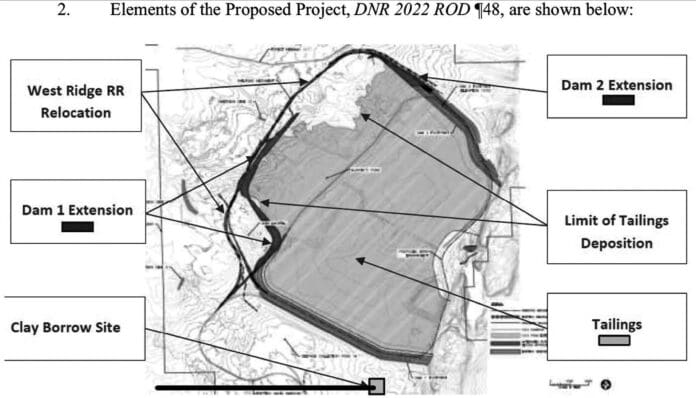

The recent expansion plans for Mile Post 7, proposed by Northshore Mining/ Cliffs, call for “relocating the existing railroad embankment, extending Dams 1 and 2, constructing a Dam 1 rail switchback, and excavating clay from a borrow pit for dam construction.” The project also includes approximately 20,665 linear feet of stream mitigation at six separate sites. Water Legacy, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, The Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, the Sierra Club North Star Chapter and others have requested a new ESI from the DNR prior to the proposed expansion moving forward. The Mile Post 7 site holds approximately 119 million long tons of tailings. Expansion would add an additional 562 million long tons to the sludge that is already there.

The DNR responded to the request in a Record of Decision dated March 4, 2024. In the news release describing that decision, the DNR denied the need for a new EIS, saying, ”Because the project proposes to use the remaining capacity of the tailings basin studied in the original EIS for the facility, and subsequently authorized by applicable permits, the DNR does not consider the project to be an expansion of the Mile Post 7 tailings basin. The tailings basin dams are subject to extensive regulatory oversight pursuant to the DNR’s Master Permit, issued by the agency pursuant to a decision by the Minnesota Supreme Court in 1977.

Another DNR document reads, “The DNR has concluded that an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is not required because the project does not have the potential for significant environmental effects. The justification for this determination is contained in the Record of Decision. The Record of Decision also contains the Department’s responses to all written comments received on the Environmental Assessment Worksheet during the 30-day public review and comment period (held April 18 to May 18 of 2023). Issuing this Record of Decision concludes the state environmental review process for this project according to the State Environmental Review rules, Minnesota Rules part 4410.1000 to 4410.1700. This project can proceed to permitting and approvals.”

Maccabee, citing the fact that data on the impacts of a possible dam breach were redacted by the DNR before they were provided to the public, stated that “the public hasn’t been given a clue on the environmental impact of this expansion. DNR has failed to describe either the probability or extent of harm from dam failure in its decision.” She also pointed out the apparent lack of transparency from a government agency that people expect to inform and protect them when it comes to potential environmental threats.

All of this raises quite a number of questions that the public deserves to have clear answers to before expansion of the Mile Post 7 tailings pond takes place.

• Why is DNR insisting that they don’t consider the project to be an expansion of the site when the height of the tailings dams, length of the dams, and sheer volume of tailings stored will all be increased?

• Why would the DNR deny a request for a current EIS and green light a tailings pond expansion project by relying on a report for renewal that was issued 47 years ago?

• Technology and construction practices for tailings basins have improved since 1974. Shouldn’t the public know whether these technological improvements would increase safety at the site?

• The Mile Post 7 tailings basin will be a permanent waste storage facility. How specifically will the site be monitored for safety and what plan could possibly be realistic to ensure dam safety for hundreds of years after Northshore’s mining operation shuts down?

• Does the public have any recourse other than going to court, in light of the lack of transparency and DNR’s failure to consider risks and alternatives?

It always helps when we can learn from history. Readers may want to research the way communities around Polley and Quesnel Lakes, in British Columbia, were impacted in the wake of the Mount Polley tailings dam breach that happened in 2014. Like Silver Bay and surrounding communities, the people living near the Mount Polley tailings dam depended on mining and tourism for their livelihood. Clearly, Northshore Mining is important to the people and economy of the region, but so is Lake Superior. We deserve environmental review of the Mile Post 7 expansion project and a serious look at safer alternatives prior to work actually beginning.