“We have Nancy Hansen here to talk about moose tonight,” said Julie Johnson, secretary for the Advocates for the Knife River Watershed (AKRW). “She’s kind of our carrot to get you all to our annual meeting. Moose are a popular topic!”

I admit, that was what initially caught my eye about the assignment to attend the meeting and presentation. But as the meeting began, my attention shifted to a map of the Knife River Watershed on the wall. Its vastness made it clear just how vital this 54,000-acre area is to the ecosystem—and why the AKRW is so passionate about protecting it.

Just over half of the Knife River Watershed is owned by the state, St. Louis County, and Lake County, while the rest is privately held. The watershed drains into the Knife River, which then flows into Lake Superior. According to online sources, it contains approximately 181 miles of streams and is regarded as a prime freshwater steelhead fishery for native trout.

The ARKW, a non-profit organization, was founded in 2011. Johnson noted, “A lot of groups like this die after just a few years. We’ve been able to stay together for 14 years.”

According to the group’s website, akrw.org, AKRW’s mission is “to be a citizen voice for the private and public land use decisions that affect the watershed ecosystem.” Their vision is a collaborative community that “strives to protect and sustain the health and stability of the watershed for present and future generations.”

Chairperson Shary Zoff addressed the attendees, reflecting on the group’s accomplishments for 2024.

“What struck me as I was looking over the past years of doing the year-in-review, it’s kind of nice to do that. We’re sticking with our mission and our goals. There’s continuity,” she said. “We did what we said we were going to and that kind of felt good.”

Those goals include:

• To conduct educational and outreach activities that increase public awareness of policies and practices that affect the Knife River watershed,

• To promote and engage in activities that can improve water quality in the Knife River watershed,

• To serve as a forum for citizens voices in private and public land use decisions that affect the watershed ecosystem, and

• To provide pertinent facts to agencies, elected officials and the public regarding land use decisions that affect the ecosystem in the Knife River watershed

“Our focus remained with where ’23 left off with ecosystem health and keeping the big picture in the forefront of our minds as we continue to educate us all in the health of the watershed,” Zoff said.

Looking ahead to 2025, Zoff projected, “We will continue our trajectory to try to weave all the different agencies involved in the watershed together and also continue to educate ourselves and our members on the importance of a whole ecosystem approach.”

As part of that effort, the group was excited to welcome Nancy Hansen, a Minnesota DNR Area Wildlife Manager based in Two Harbors, to the meeting for an informal talk on moose in Minnesota.

Hansen has been with the DNR for about 25 years, beginning as a creel clerk for the Fisheries department. During that time, she fell in love with the North Shore. After working as a Wildlife Technician in northwest Minnesota, she returned to the North Shore in 2007 and became involved in the aerial moose survey.

“That is by far the most exciting part of the work I do,” she told the group in her introduction. Hansen is deeply involved in moose habitat partnerships and oversees the North Shore from the French River to the Grand Portage Reservation and the Canadian border.

With the help of two assistants, her work extends to Pequaywan Lake, Finland, Fairbanks, Isabella, and the end of the Gunflint Trail.

According to Hansen, “My staff and I spend a lot of time talking to the public about wildlife concerns and nuisance issues involving bears, deer, foxes, woodchucks, etc., general wildlife identification, as well as answering hunting and habitat questions. We give presentations when requested. We spend a lot of time on forest management collaboration with DNR Forestry and help with habitat or facility projects involving neighboring offices, conservation organizations, other public agencies, and our tribal agency partners. Our work also involves completing several different wildlife surveys annually and occasionally assisting with research projects. That’s the fun stuff!”

The most recent aerial study concluded just a couple of weeks ago. Typically conducted right after the new year, this winter’s survey was delayed due to low snowfall.

“Moose are a very dark animal and you’re looking for them through trees so you really need as much snow as you can on the ground to make them pop out,” Hansen explained.

In 2006, the estimated moose population in Northern Minnesota was 8,800. Nowadays, the “middle” number of the estimate has remained stable at around 3,400-3,500. The results of the most recent survey will take some time to be reviewed, as is typical with a sample study.

The survey samples a random 10% of 400 plots. There are 9 permanent habitats that have been impacted by wildfire, prescribed fire, and forestry management. According to Hansen, “We try to evaluate what the moose’s response is to that disturbance or treatment.”

Fire and logging were key factors that allowed moose to flourish in Northern Minnesota in the late 1800s, as they thrived on the aspen and birch that regrew after the land was disturbed.

“These large, young regenerating forest areas are great for moose habitat,” Hansen said, adding that moose need to consume about 73 pounds of food a day to support their mass. Bulls typically weigh between 800 and 1,200 pounds, while cows range from 600 to 800 pounds.

Around 1912, it was first recorded that moose were exhibiting strange behavior, such as wandering aimlessly and showing no fear of humans. This was later linked to the influx of white-tailed deer in the area.

Due to poorly regulated hunting, poaching, and disease, the moose population dwindled to around 2,500. In 1922, moose hunting season was closed. In the 1930s, brain worms were discovered in moose, but the connection to the growing white-tailed deer population had yet to be made.

Parelaphostrongylus tenuis is a parasitic nematode worm that infects white-tailed deer without causing harm to its host. However, when the worm infects moose, elk, and caribou through infected snails, it causes neurological damage, which can be detrimental to the moose.

In addition to the devastating effects of brain worms, moose are also plagued by winter ticks. Take it from me—do not look up winter ticks on the internet.

“If you saw them, you’d probably be alarmed at how big they can get,” Hansen said, noting that moose can host thousands of winter ticks at a time. Some moose have been known to rub off their hide to remove the ticks, resulting in a “white moose” or “ghost moose.” The ticks cause anemia, making the moose more vulnerable to predation. As one can imagine, the ticks are especially harsh on the calves.

Despite these hardships, the moose population grew, and by 1967, it was estimated that 7,000 moose were living between northeastern and northwestern Minnesota, about 4 per square mile.

Hunting was reopened in 1971, with groups of four allowed per tag. About 37,000 hunters applied for a license, and 400 were selected to hunt. That year, 374 moose were harvested. By 1983, it was estimated that as many as 1,179 moose were hunted.

In the 1990s, the moose population began to decline again in northwestern Minnesota. In the late ‘90s, VHF collars were used to track moose in the area. However, after the tragic loss of a state conservation officer and graduate student during an aerial survey, combined with a low moose count, the moose population has not been studied since 2007, when only 100 moose remained.

In northeastern Minnesota, VHF collars were introduced in 2002. From that study, researchers determined a 21% mortality rate in moose, which was twice the normal rate. Due to the need for aerial monitoring of VHF-collared moose, real-time research was difficult to conduct. While some deaths could be attributed to car accidents and wolves, 49% of the causes of death remained unknown.

A wildlife health program specialist came up with the idea to ask hunters to help provide samples of moose tissue for research.

“A lot of other states kind of laughed at that and thought we wouldn’t get a lot of cooperation,” Hansen reported. “We had great cooperation. Our hunters were fabulous, and we were able to get a lot of good tissue samples of moose.”

In 2013, northeastern Minnesota began a GPS study, placing 173 collars on moose that could be monitored via cell phone. If a moose remained stationary for an extended period, the GPS signal would alert members of the study.

“We found that 65% of our moose that we responded to that died had died from some type of health problems. 30% was predation,” said Hansen. “We don’t know the exact infection rate. We’ve had opportunistic moose that we’ve sampled from road kills or something like that. The infection of brain worm might be as high as 45% and then from our collared moose it was in the 20%s.”

If you see a moose that is not acting normal, it is important to report it to the local DNR.

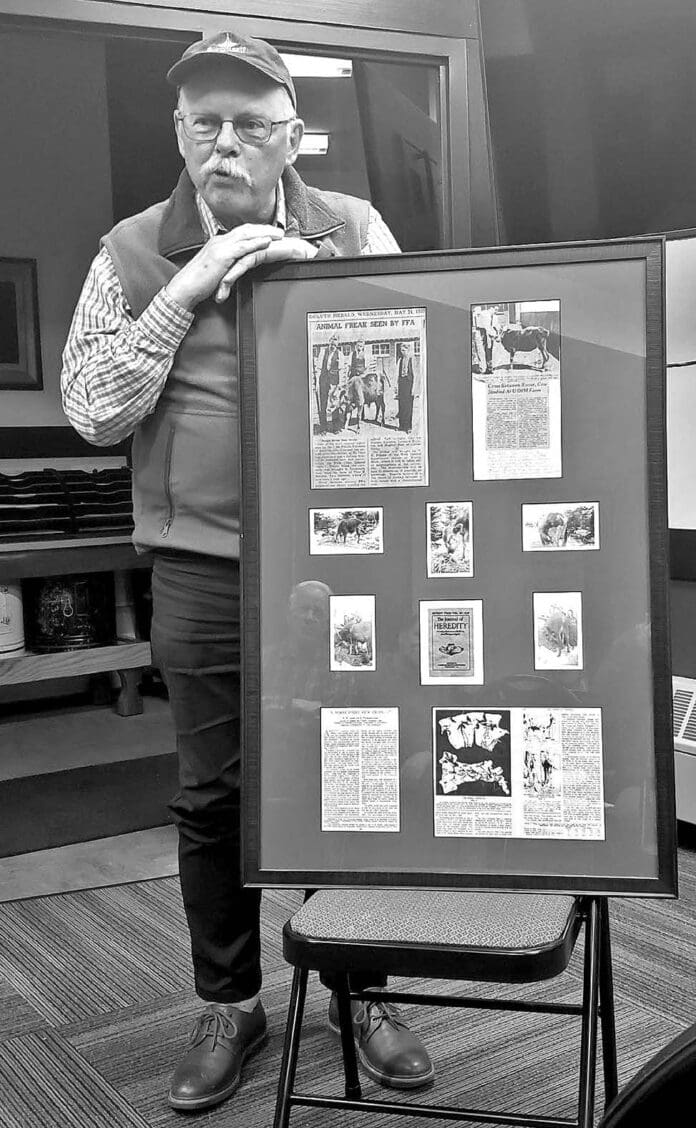

After the presentation, but before the AKRW members voted on this year’s board members, a gentleman shared a framed collection of news clippings and, may I say, “moose-cellaneous” items related to a strange and special calf born in the area. The headlines read, “Cross Between Moose, Cow Studied at U of M Farm” and “Animal Freak Seen by FFA.”

Though he admitted that the scientists were not convinced of the unusual pairing, it was still quite a fun story to hear! The Advocates for the Knife River Watershed have a Facebook page and can also be found at AKRW.org. New members are always welcome. Dues are $20 per year.